One of the few positive points of the Corona-crisis is that it provides an opportunity for reflection. For me, this included looking at the design considerations applied ages ago and the ones we use now. What are the differences and what is still valid?

A lesson from the Corona-outbreak is not to take anything for granted. In developed countries, the emphasis is very much on achieving maximum efficiency and effectiveness, in developing countries my design criteria focussed on maximum resilience. That means shifting from looking at “what can go right” to “what can go wrong”.

Nowadays we love to go for the new technical stuff, with buzzwords like big data, disruptive technology, machine learning, etc. In the process, we tend to forget the “what can go wrong”-side of things. Of course, we talk of co-design, but in practice, this is dealt with as a step in the process and then we go on with the technical things that make us so happy.

The danger is that this creates a mismatch between the “technical solution” and its successful long-term application. Not that there is anything wrong with technology, but things should be kept in perspective.

Here are some design considerations from a long time ago that still apply, in my opinion, and are maybe forgotten in our desire to hit the ball out of the park. This effect is reinforced by the fact that most innovation funding is project-based and we, therefore, want to show quick results.

- Cost reduction: This applies to the introduction of new technology that improves the current situation (e.g. platforms with services derived from big data), but in such a way that the solution is sustainable. Keeping the costs low, instead of counting on a high revenue – high-cost scenario (that maximizes profit), reduces the risk of failure. This focus can even lead to additional design gains, where e.g. earthquake-resistant water tanks and acid groundwater-proof concrete well elements turn out to be cheaper than off-the-shelf solutions.

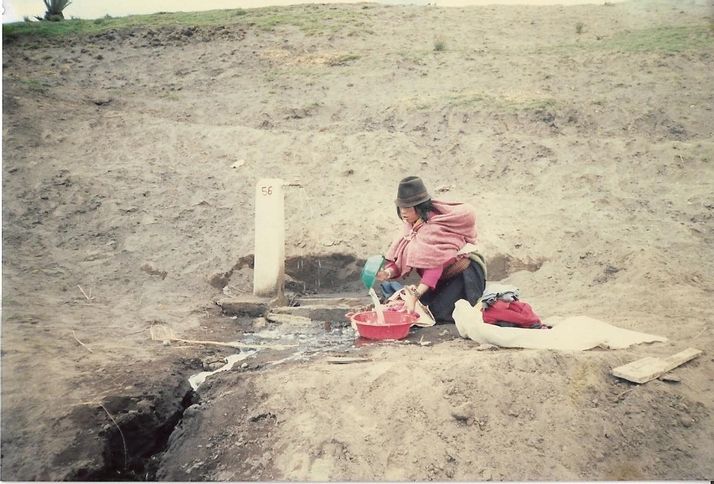

- Anti-fragility: This term, coined by Nassim Taleb in his book Antifragile, deals not only with building in redundancy (look at the problems we have now with getting sufficient Corona-testing kits and intensive care beds and equipment in hospitals), but also with keeping the right purpose in mind. That means that wells should be equipped with buckets instead of handpumps, when you know that remote villages will never get visits from maintenance and repair teams. It also refers to the concept of granularity (thanks, Jack Dangermond of ESRI, for a discussion on this, already a long time ago). Design with granularity in mind reduces the risk that when one element malfunctions the whole system breaks down.

Long-term perspective: We should take the time (that we usually think we do not have) to design for the long-term and really involve the people concerned. They then become the owners of the solution, e.g. indigenous communities that get a “yes-we-can” spirit and go for installation of electricity after the drinking water system is completed. On the other hand, just as adjustments to the Corona-situation takes time for us, acceptance of new solutions also is a process that may take longer than anticipated. E.g. by involving everyone you avoid situations where the location of a planned well is “cursed”, because the local traditional well-diggers were not consulted.

And, of course, we are “human, all too human”: after a while, we will forget what this Corona-thing was all about. But still, the crisis gives us a good opportunity to give co-design and innovation a new look.

Written by Mark Noort